|

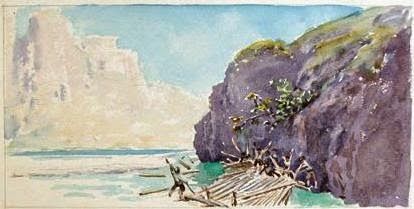

| A rainy Perarolo looking south [© Peter Alexander Gray 2012] |

However, we can find from records what it was like to travel on a commercial raft leaving Perarolo for Codissago.

The travel writer Napoleone Cozzi described such a journey made in August 1898, and his description has never been bettered:

Of the first moments, there remains only a confused memory: the sharp command of the head zattiere, the strike of oar that

with resolve directs us in the middle of the river, the chorus

of the salutes and the wishes that rise from the bank; at the first bend

Perarolo disappears.

|

| Napoleone Cozzi's 19C sketch of a three-section zattera |

What a feeling! What a

profusion of ever-new wonders, how many unexpected beauties, what lights, what

coolness!

The zattera normally follows the principal

trunk of the river; now it winds in narrow or wide curves, silent and fast; it

passes out under a rock of lead, it pushes through the foliage, it goes into a

gorge, then exits free into a wide river basin.

At the bottom, at the

opening of the valley that catches the eye, the last violet crags seem to

compete among themselves to be first to show their details; they are made grey,

they offer the cleanest contour, the most definite shades; they cast on the margins

of still water their trembling reflections, they pass quickly, showing patches

of blossom, scrubs of firs, unexpected rivulets, landslides, paths, valley

dwellers, ravines, torn banks, vagueness in all the forms; they disappear at a

turning to reappear later behind us, distant, with their forms made smaller,

confused, with the forests pale, with their lines lost among the light shades.

We pass rustic

cottages, isolated or in groups, pass flour mills, bridges, sawmills;

valleys supply secondary tributaries that add to the increasing greatness of the

Piave, with cascades, with a last fall or by just gently flowing down through

their flat beds of gravel.

Up there aloft, on the road that follows the line of the river... holidaymakers look us bewildered, answering our mimed greetings with the waving of handkerchiefs.

|

| Heading downriver [© Peter Alexander Gray 1998] |

The road which I cycled in 1998 followed the same river, but was a much wider, modern road. The flow of the Piave being much reduced nowadays can make the river (lower left-hand corner) more difficult to photograph from the road.

I hadn't time to stop and look at the famous Madonna della Salute chapel at Macchietto, as I had set off from Cima Sappada the morning of that same day (August 1998), and visited Pieve and Perarolo en route.

It was difficult to realise, as we drove along amid scenes of peacefulness and beauty, the terrible fighting that took place here so recently. As we approached Riccorbo [sic] there was just room for the road to pass under the cliffs that overhung the Piave. Here the leader Calvi barricaded road and river, and had the cliffs undermined as at Tovanella, and men stationed with levers to hurl the shattered rocks upon the enemy, When the Austrians with disastrous results. In the pause that ensued a flag of truce was displayed by the enemy, and Calvi caused hostilities to cease, and prepared to speak with the Austrian General Sturmer, when the cry of treachery arose. Under cover of the flag the Austrians were scaling the cliffs above. The Cadorini fought with redoubled energy, and the Austrians, 5000 strong, were forced to retire. General Stiirmer praised the heroism of the Cadorini, and was more than astonished afterwards to learn that they were not regular soldiers, but only undisciplined mountaineers.

I hadn't time to stop and look at the famous Madonna della Salute chapel at Macchietto, as I had set off from Cima Sappada the morning of that same day (August 1998), and visited Pieve and Perarolo en route.

|

| The Piave valley between Macchietto and Ospitale Carte e Piante Turistiche Tobacco sheet 1 |

The travel writer the Reverend Robertson, travelling north through the valley in the late nineteenth century, wrote:

The next two villages, Rivalgo and Riccorbo [sic], have a place in both ancient and modern history. Both are mentioned in documents of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries in connection with the wood trade, and both are famous in the struggle to throw off Austrian rule in 1848. Just outside the former place is another obelisk of red stone.

|

| Obelisk from 1848. The names of the Cadorini were added 150 years later |

In my diary of 1998 I wrote:

It’s half past four

and I am at Rivalgo. Looking around, the whole place has been blasted by [debris thrown up by] passing road traffic. What a great shame – it was was clearly once a quaint old town.

|

| The church at Rivalgo - image © Franco Baldissarutti |

|

| The church at Rivalgo.Image © Franco Baldissarutti |

I am most grateful to Franco Baldissatrutti for permission to use these images.

There is one more entry in my diary relating to Rivalgo.

Huge iron gate to my right [on the opposite side of the road] with CJM on the top – wonder if it is someone descended from the Malcolm family of Longarone?

|

| Gate at Rivalgo with initials 'CJM' Image © Franco Baldissarutti |

The diary continues:

Looking down the valley there are sand quarries. I’m only about a third a way down [the valley towards Codissago] so need to press on towards Ospitale.

There is a huge rock in the river north of Ospitale - the Sas Levado.

|

| The Sas Levado [© Peter Alexander Gray 1998] |

Here the zattere were pushed into a narrow channel, where rocks and submerged branches could damage the craft. Once past the Sas Levado the rafts plunged down into safer waters - if they were still in one piece!

Franco Losso in his informative article Da Codissago a Perarolo says 'Along the first stage [from Perarolo to Codissago], with so many risky points, the Sas Levado was, for the zattieri, perhaps the one of the most imminent danger...

All Napoleone Cozzi's beautiful watercolour illustrations (the full-size portfolios) are held in the collections at the Centro Regionale di Catalogazione e Restauro dei Beni Culturali.

There were numerous cataracts and falls along the river. Napoleone Cozzi's trip was a good one:

But these impatiences, this restlessness, these nervousness, are compensated

at some points by exuberance, the most beautiful, the most grand of the

journey, that don't have comparison, that raise above every

superlative, over

every well-worn cliché: The falls!

They are five of it or six of them.

What a strange impression the first time! That double near Longerone is sublime!

By now at a certain distance, the

course of the river seems truncated by

a dam that crosses it leaving a narrow outlet over which the enormous liquid

mass falls with a roar. Looking within into one’s thoughts the whole desire is

to believe that the zattera will

surely be held back or diverted by whoever known means one can devise, from who

knows what providential source. Run free

instead and dare the Devil! It is an unworthiness; it must be a big a colossal

jest or a madness without name; the zattèri

must be crazy. There is by now no escape; in a few moments we will be absorbed,

swallowed. Speed still increases, the roar becomes more and more deafening. You

want to cover your face with your hands, would want to rebel and make a

desperate jump for the fleeing gravel banks.

We are there: The two front men leave the oars, they turn them and fix

them with ropes; the first part of the zattera

squeals, it folds up, it falls, to disappear. Behind us upright, fierce,

impassive as the god of the storms, the head zattiere directs a last stroke of the oar, then lowers it and now also

secures it. Here is the instant: Gods of

the abyss! The support goes from under us; fingers grab on to the beams, become

entangled with the ropes, with the cords, and with a big cry of passion we

sink, intoxicated with emotion, licked up by a wave of foam, wound by a

downpour of silver spray.

The stretch between Perarolo and Longarone lasts a couple of hours and

is the most beautiful in life. It is a mix of enchanting feelings that are happening fast and

continuous. It is a dream radiated by delicious images. It is a jubilation, of which a single recollection is sufficient to cure

all the melancholies of man’s life and it is a wonder that it is not the

preferred amusement of half of humanity.

Note: This blog supports readers of The Door of Perarolo, a historical novel set in Cadore, Italy in the early nineteenth century. You may examine feedback from readers in the UK here and in the US here. The Door of Perarolo is a Kindle ebook comprising 140 chapters. It can be downloaded from Amazon sites worldwide. The launch post of this blog gives further details. The second post provides links to maps, etc.